On the face of it this is a story about a disappointing trip to Indianapolis in 1952. But it also serves as an F1 chassis design progression discussion. That part of the story takes us from ladders to spaceframes over the next five years.

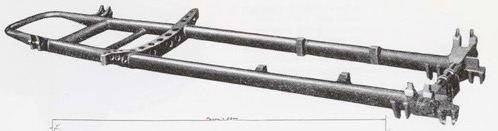

Enzo entered top formula single seater racing in 1948. The formula at that time was for either 4.5 litre naturally aspirated engines or 1.5 litre supercharged ones. His first cars were 1.5 V12s. (Their 125 model designation refers to the capacity of one cylinder. Multiply it up by 12 to get 1500cc). Their chassis were simple ladder frames. The basic frame is shown below. Keep this picture in mind as a version of it turns up in one form or another in the heart of just about every 1950’s F1 Ferrari.

To this frame a mesh of small upper body support tubes were added. These are not chassis tubes as such and carry no bending loads. A dressed up 125C frame is shown on the right. 4.5 litre versions of this frame continued in service until the end of 1951.At the end of that year F1 was thrown into disarray. Spiralling costs and a lack of quality entries saw the pre-existing formula 2 take over as the premier class for the next two years. This left Enzo in an interesting place. His very expensive stock of formula one machines would not see much use in Europe.

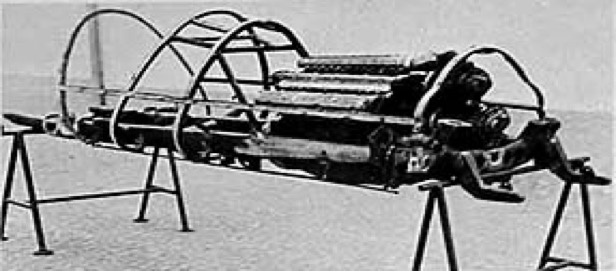

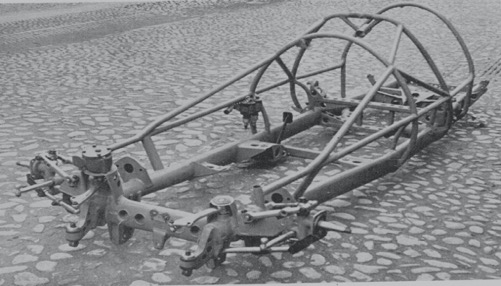

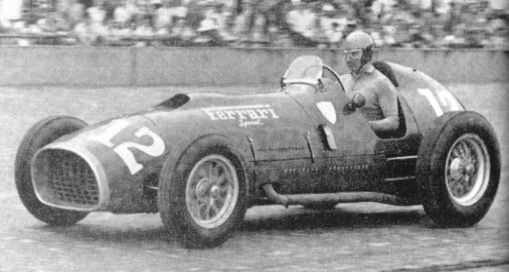

But they could be ran at Indianapolis (with a slight reduction in engine capacity), and better still Indy still counted as a world championship race. He could even unload some of his now redundant F1 machines. And so it was. Three of the old cars were adapted for American owners with chassis strengthening upgrades to cope with the continuous high loads from the Indy bankings. This extra super-structure tubing increased the bending strength of the frames but added little to their torsional stiffness. But Alberto Ascari’s factory car chassis was altogether different. While outwardly similar this did away with the big tube ladder frame and instead had a multi-tubular side trusses, almost but not yet a space frame arrangement. This chassis is identified on its manufacturer’s website (GILCO) as being a 1952 Formula One frame, so this was probably its originally intended use, a tantalising might have been had the old formula continued. This frame would have had much improved bending and torsional strengths. These two frames are shown below.

The trip to America was a promise unfulfilled. The Ferrari V12’s had low engine torque coming off the turns and the American owners had trouble getting to grips with the different driving techniques required for these cars. Due to Ascari’s new car proving temperamental they received very little factory support and none qualified for the race. (All three of these cars survive to this day, having been wheeled into various garages and left there in 1952). But the factory car was a different story. While the temperamental practice gave a mid grid starting position it also gave a well sorted race car. Ascari made up places early and settled into a comfortable pace in the second group of runners. His early pace was on a par with that of the eventual winner and his pit knew he was in with a chance. Their disappointment was palpable when, due to the constant high loads on the bankings a rear wheel (or hub – accounts vary) collapsed 40 laps into the race. Maybe if they had used solid alloy wheels like the Americans, instead of the factory wires, the story may have had a happy ending.

The factory was not discouraged. They were back again in 1954 (this was intended to be 1953 but the car was not ready in time). This time with a more powerful 3 litre supercharged engine and a modified car layout. Much of the fuel was transferred to side tanks, with a smaller rear tank. Alas the car did not qualify. Some claim that the 1952 Ascari chassis was recycled for 1953/4, but a photo of its chassis while it it was being restored shows a quite different side truss treatment and front suspension hoop arrangement, so it was most likely a new frame. The ’52 and the “54 cars are shown below.

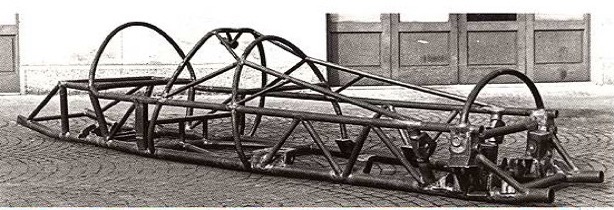

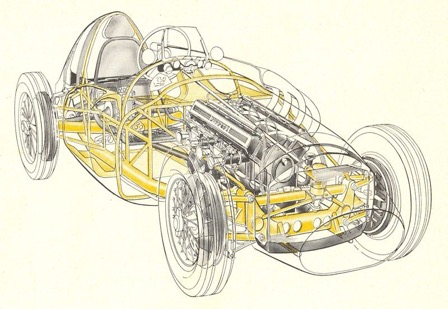

These side truss and side tank features were also used for the ’53-’55 F1 Squallos. (See below left). The Squallo was based on the previous years formula 2 ladder chassis. On the cutaway you can see that the original large ladder tubes are still there but with an additional top truss imposed on them. The short wheelbase low polar moment design of the Squallo resulted in a design ahead of the tyre technology of its time. Its intended neutral handling translated into a car that gave no warning of which end might break away first, a propensity cured by softening the front end with coil springs, building some mechanical understeer into the suspension., and carrying some fuel in a rear tank. The car was now stable in a corner but slow, (strong understeer is like slapping the brakes on). Its lack of success nearly drove Ferrari to the wall. A situation only remedied by the transfer of the also financially exhausted Lancia D50’s, with bag of Fiat backing, to Ferrari at the end of 1955.

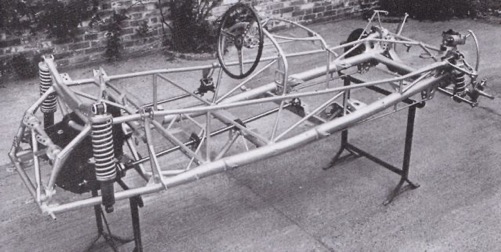

The next true Ferrari F1 chassis was that of the 246 Dino cars used of ’58 -’60 (above right). This one is the ex Pat Hoare NZ Dino frame when under restoration. The way in which the basic ladder is integrated into this new frame is clear to see. This Dino 246 frame is not yet a space frame but it is as close to one as Ferrari ever got. Note that the car designation system has changed. The 24 bit now refers to the engine size (2.4 litres) and the 6 refers to the number of cylinders.

FOOTNOTE:

While still involved with the BRM project, and prior to building his Vanwalls, Tony Vandervell ran a series of Ferrari’s as a learning exercise. It was one of these, in a 1951 non-championship race, that Reg Parnell gave the 158/159 Alfa Romeos their first ever defeat. Gonzalez’s famous 375 victory at the British Grand Prix came latter in the season.

The first three Thinwall Specials were like Captain Cook’s axe. The second one was a re-chassied version of the first, and third of them was the second one re-engined. The first one was a short wheelbase 1.5 litre supercharged 125. These were iffy handlers and the first Thinwall was soon crashed. Back it went to Maranello for upgrading onto a longer wheelbase frame. One race and one engine failure later this car was returned to the factory to have the 125 supercharged engine replaced by a 4.5 litre naturally aspirated one. (This was the car that gave Parnell his victory over the Alfa’s).

When Vandervell imported his first car he sought to avoid import duties and sales tax by claiming that the car was to be used for experimental purposes. Customs were quite happy with that, provided it was never actually raced, but Vandervell wasn’t. So he bit the bullet and paid up. We can reasonably guess that its upgrades and modifications never changed its description as far as HM customs were concerned). The last Thinwall was a complete new car on an Indy chassis frame. Restored/rebuilt Thinwalls 3 and 4 exist to this day. The photo below shows the different chassis treatments. Thinwall 3 in the foreground is based on a big tube ladder frame, Thinwall 4 in the background is on the Indy frame.