The last article in this series finished with the thought that twin tube ladder chassis’ logically lead to a monocoque. But that is not how it came about.

Definitions vary as to what constitutes a monocoque, but the common thread is that it is a structure in which the skin and the frame are one and the same thing. So we are looking for a stressed skin structure, not just the absence of a separate chassis. Aircraft not only have to be strong, they also have to be light, so trusses and space frames were part of aircraft design right from the start. Enclosing such a frame in a fabric skin reduces drag by smoothing and sealing the frame but adds nothing to its structural strength. It is a small step from there to amalgamate the skin with the frame and it did not take long for that step to be taken.

The first use of monocoque construction in aviation is attributed to a Swiss marine engineer, Eugene Ruchonnet, who built such an aircraft (nicknamed the Cigare) in 1911. Photograph below.

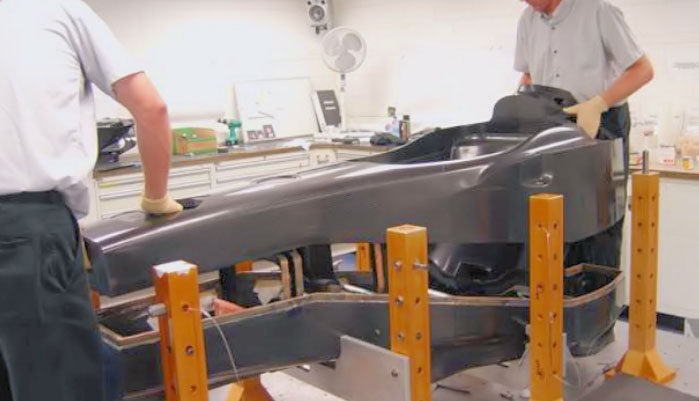

This had a fuselage constructed as two diagonally planked half hulls joined over internal bulkheads. (If you built up model plastic aeroplanes as a youngster then you will know how this goes), Otherwise imagine two rowing skiff hulls joined gunwale to gunwale. (The origin of the double diagonal planking hull making technique is attributed to 19th century Scottish shipbuilders).

The more important question for us petrol heads is who first applied this technique to racing cars? The answer is not Colin Chapman. It did take a while to get there with another step along the way, again borrowed from the aircraft boys.

Wooden monocoque aircraft were strong and light, and very soon some-one thought of doing the same thing in metal (a big pipe in the sky with wings on it). It didn’t take long to work out that a lighter pipe for the same strength can be made by busing a thinner skin with stringers along its length to help the skins keep their shape under load. All skins will try to bow inwards or outwards under loads, thin ones much more so. The stringers prevent the bowing. Better still the skins no longer need to be curved.

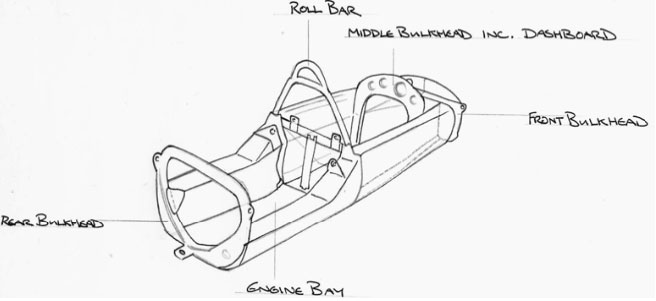

These days the aircraft boys call this construction semi-monocoque, as there is some sort of underlying frame supporting the stressed skin, but we need not make such a distinction. A mono-place aircraft needs only one relatively small hole in it to contain the pilot, but a car is more complicated, needing holes for the engine and passengers as well. It also need strong points each end to absorb the suspension loads. An aircraft fuselage is supported by its wings in the centre and tries to bow downwards at its ends, a car is supported by its suspension at each end and tries to bow downwards in the centre. So the aircraft analogy only takes us so far.

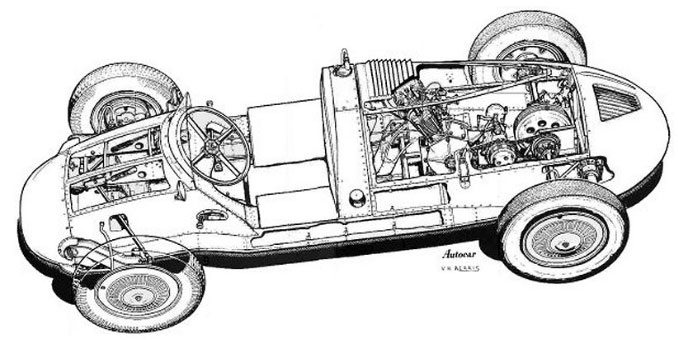

The first stressed skin car was not even a racer, it was a production light car made into a racer by Louis Chevrolet for the 1915 Indy 500. The Cornelian was a skimpy “cycle car” in the parlance of the day. Its base tub was made from a “U” shape folding with stringers along its length. It had independent suspension front and rear.

The skin was attached to bulkheads at the front (to provide mounts for the front suspension and the front of the engine), in the middle ahead of the driver’s feet (to which the rear engine mounts and driver controls were attached), and at the rear(to which the rear suspension and the fuel tank were attached. A look into the cockpit shows how a load bearing scuttle above the driver’s legs completed the job. As another modern touch the solid mounted engine is part of the load bearing structure of the car.

An open top channel is neither as strong in bending, nor as torsionally stiff, as a closed one. Never the less variations on this theme continued to appear for the next forty years or so (e.g. Lancia and Voisin in the 20’s, Issigonis in the 30’s, Bond and Killeen in the 50’s) but the technique did not find racing favour. Possibly for the reasons given by Colin Chapman to Tom Killeen in the mid 1950’s.

“It is axiomatic with stressed skin structures that the loads are fed into this structure in as widely distributed and as uniform a manner as possible, and nearly all the load reactions such as engine, spring, shock absorber and suspension mountings have to carry power loads of fairly high magnitude and, therefore, most of the structure system does not lend itself to this anchorage”

He was later to change his mind, and the reason for doing so was already at hand. In 1949 a Canadian motor cycle racer called Spike Rhiando had commissioned a very special 500 cc formula car. His “Trimax” was built along aircraft lines as well. But this time there was a way of getting around the problems of a single skin with big holes in it. It was built as two side tubes, not one single one.

Before long Jaguar joined in with their central monocoque “D” type, and a few other examples along the way, so did Colin Chapman with the Lotus 25. Compare the cutaway of the Trimax (on the left) with the drawing of a 25 (on the right), and note the similarities between his car and Spike’s. Chapman

had put aside his rejection of the stressed skin concept just a few years earlier and now claimed this variation of the idea as his own.

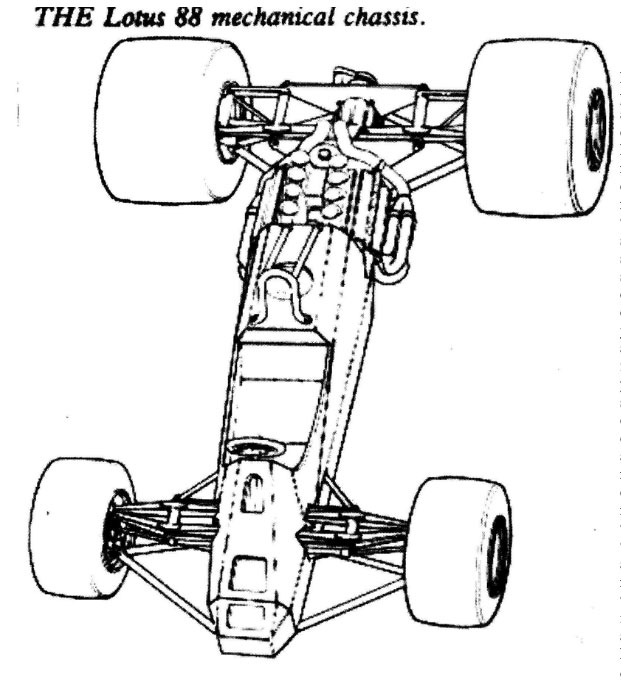

But our story is note quite done. The extra internal skins of a two tube structure will always make it heavier than a single tube one. So, harking back to the Cornelian, when it became normal to use the engine as a structural member, hanging it onto the rear of the driver bay, then the single skin main structure came back into its own.

The later Lotus 88 shows how compact that central pipe can be. Put the fuel behind, rather than alongside the driver, and the freed up side space can now be used to generate downforce.

And to complete the cycle we can now return to the moulded half hulls glued together approach. Here it comes. (Brawn Honda 2008).

So who invented the monocoque? Most likely Eugene Ruchonnet in adapting a prior idea from a bunch of unknown Scottish boat builders.

FOOTNOTE: Life’s road can be a hard one for pioneers. Google “Avions Voisin” or “Tom Killeen Cars” to see just how challenging that road can be.